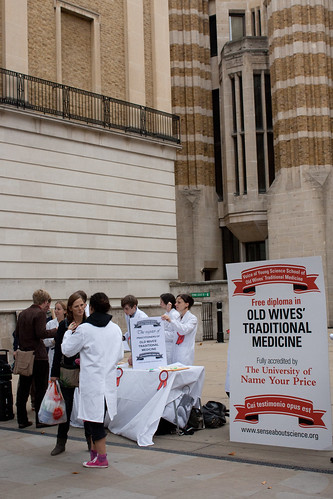

And so it is the beginning of another month, which means it’s time again for Westminster Skeptics in the Pub. This month, it was the turn of the SciencePunk, Frank Swain, to address us with a talk entitled “A critique of skepticism”. Here, he basically told us where skeptics (or the skeptic “movement”, if that exists) are going wrong in engaging with others. I think most of us probably have an uneasy feeling about things we have seen done in the name of skepticism and how we are perceived by “non-skeptics”, such as my first thoughts on skeptics insular nature last month.

In a way, I think Frank was putting out there our own “inconvenient truth”, that we dimly recognised before. The genius was in his delivery, which was a well-illustrated, persuasive and coherent argument. I’ve said this before, but it is a mark of great speaker at SitP, when we carry on discussing their talk long after fact, because it has been that thought-provoking.

What follows is just a few of my favourite quotes from the presentation. I never take enough notes for a full round-up and there are many who are better at it than I anyway.

What are the KPIs of skepticism?

- Who are you talking to?

- Who is listening?

- Whose mind is changed?

I’m pretty sure anything I’ve written hasn’t changed any minds. Why? I write for those who already think like me. Not on purpose, but because actually challenging someone’s opinion, in writing, is difficult. What is worse is that I hadn’t even considered this until last night.

“A Facebook group or Twitter hashtag is not a campaign.”

It shows a groundswell of support from those already in the know, but it doesn’t change minds or engage. It is people agreeing with their mates.

Undeniably true.

I think this is also the time that Frank introduced the “Mum” test: how would you explain it to your mum and would she care? A useful teaching technique that should be applied to skepticism more. To me, that indicates a danger of talking down to people and coming across as superior – a point that is later addressed.

Facts do not speak for themselves. We have a fetishism for facts.

How many people have heard or used “the plural of anecdote is not data”? *many hands go up* – “instead it’s a convincing argument”.

Whilst we can ask for evidence until we are blue in the face, it only convinces people that make evidenced-based decisions. Anecdotes persuade a lot more people. Frank’s example here was; user reviews on Amazon – many of us use them to make purchasing decisions based on anecdote, because we trust others. Also, how many of us can prove that the Earth orbits the Sun? I guess anecdotes/non-first hand evidence is more pervasive that we’d like to think.

Arguing from facts is cowardly. You’re going in with the knowledge that you’re right. Arrogance will show. (I didn’t note this verbatim, so relied on a tweet for wording)

I struggle to agree with this, because people don’t go into arguments knowing they are wrong. Each party tends to believe (to the extent that they know) they are right. However, I can definitely buy the idea that arguing arrogantly doesn’t work.

This is why I have a problem with the concept that skeptics are teaching or enlightening people. It implies a hierarchy where skeptics are above those they are talking to, who are in turn in some way stupid or primitive.

That leads on to what I think was the take-home message; just because you have evidence, doesn’t mean you are better, or even right.

In no way was that a complete report of the talk. It is only the bits I found most interesting and challenging (and the bits I had notes for). Most notably I missed out all of the coverage of the recent Twitter mess regarding Gillian McKeith and the level of skeptic vitriol that was shown.

I will link here to any more complete reports as they become available: