A few weeks ago, the Nobel Prizes for 2017 were announced. This year, 3 of the founders of the field I work in – cryo-EM – were honoured with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work in developing the technique of cryo-EM into something now used near routinely in labs around the world.

After the news was announced, I was asked to write a short explainer/news piece about the technique for the website The Conversation. The Conversation is a website where academics team up with professional editors to write and publish articles, so it was really nice to be asked to write for them. The resulting article is published under a Creative Commons CC-BY-ND licence so can be reused anywhere, so I’ve taken the opportunity to archive it here:

Trio behind method to visualise the molecules of life wins 2017 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

James Streetley, University of Glasgow

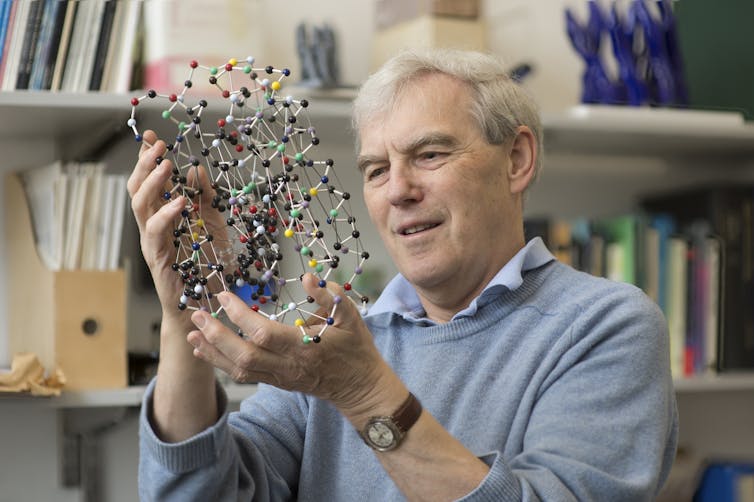

Three scientists have won the 2017 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for developing a technique that helps image biological molecules in unprecedented detail. Jacques Dubochet, from the University of Lausanne in Switzerland, Joachim Frank, from Columbia University in the US, and Richard Henderson, from the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in the UK, will share the prize sum of £831,000.

A predecessor of their method – which is known as cryo-electron microscopy – has been recognised by the Nobel committee before. The 1986 Nobel Prize in Physics was given in part to Ernst Ruska for inventing the electron microscope.

As a concept, the electron microscope is similar to a light microscope – a beam is shone through a series of lenses, then through the sample and more lenses, to form an image on a piece of film or camera sensor. Of course, in the electron microscope we are shining a beam of electrons rather than light through our sample.

Unlike light, electrons can’t travel through air – they would collide with the air molecules and get diverted away. This means the electron beam must be contained within a high vacuum system so there are no stray particles to interact with the beam. The lens system is formed of coils of copper rather than the glass lenses of a light microscope – like air, glass would scatter our beam of electrons, rather than focusing it. Instead, we can apply current through the coiled-copper lenses to create a magnet, and we can focus and shape our beam using this magnet instead.

MRC/UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE/EPA

However, the need for a high vacuum within the microscope affects what samples can be imaged. Samples need to be dry as liquids would instantly evaporate in the vacuum. Methods for preparing a biological sample like this are to dry them in a protective stain layer or embedding it in resin. However, such dehydration techniques don’t allow us to make the most of the microscope and see the finest details in our sample.

A new era of biochemistry

Cryo-electron microscopy eliminates the need for dehydration. Biological samples such as cells, viruses or proteins are simply frozen within the liquid they are in. As long as we keep the sample frozen in the microscope, the ice protects it from the harsh effects of the vacuum. However, we can’t form just any type of ice. It must be vitreous ice.

This ice doesn’t form crystals, like in a home freezer, where the water molecules rearrange into an ordered pattern. Instead, they are frozen fast enough that they stop moving as they were. It is as if we hit the pause button on liquid water. It was the discovery of how to create vitreous ice that earned Dubochet his share of the prize.

Since then, many laboratories around the world have adopted the technique of cryo-electron microscopy, aided by semi-automated machines for preparing samples within vitreous ice. The earliest work began with looking at viruses, but advances in microscopy and related technologies has seen this expand across a whole size range from tiny individual proteins (around a millionth of a centimetre), through to “molecular machines” consisting of proteins assembled together. “Motor proteins”, such as myosin, are examples of molecular machines – they are responsible for muscle contraction. It is also possible to image bacteria and sections of human cells.

By analysing these images with computers we can calculate how the particle would have looked in 3D in order to produce that image. It’s similar to looking at a shadow and working out how the object that made it looks. Devising methods to do this is part of what Frank was honoured for.

Once we have a 3D model for how a virus or molecular machine is structured, we use that to understand how it functions. Henderson was the first to show that cryo-electron microscopy could be used to obtain the most detailed of 3D models – at atomic resolution. Often, other laboratory methods can tell us “what” a molecular machine does, but with detailed 3D models, we can look inside these machines and understand “how” they do it.

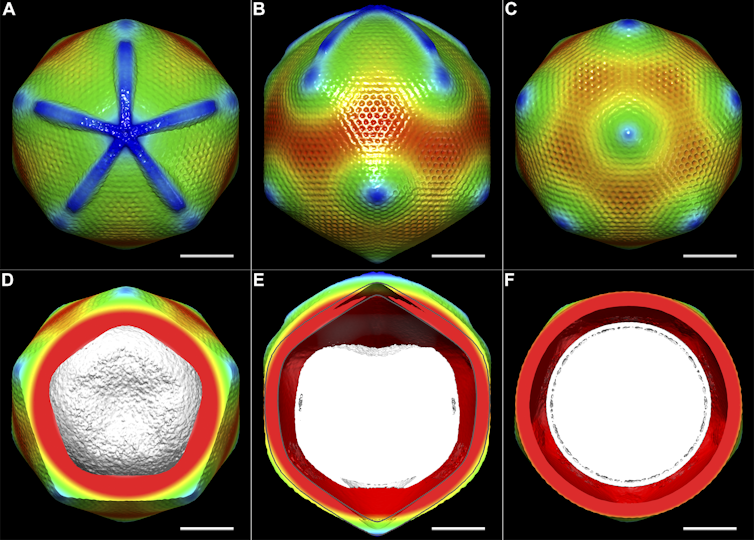

Structural Studies of the Giant Mimivirus. PLoS Biol 7(4): e1000092. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000092, CC BY-SA

Having a basic understanding of how these machines work, we can start investigating diseases. What happens when such machines don’t work? Or in the case of bacterial or viral infection, what can we do to disrupt their molecular machines? A recent example of this is the Zika virus: scientists used cryo-electron microscopy to rapidly determine the structure of the Zika virus last year. This has already led to follow-up research looking at how to find drugs against the virus. Scientists have also managed to look at proteins involved in antibiotic resistance using this method.

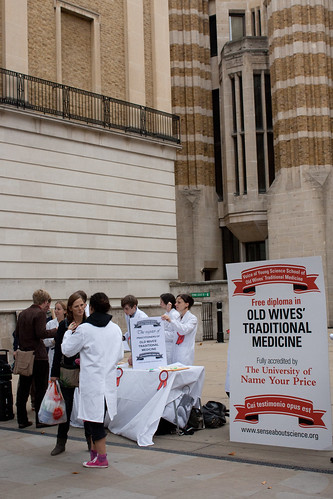

![]() The technique is already achieving results that were unthinkable a few years ago – both in terms of the small size of biological molecules that can now be imaged, and in the detail that can be seen in them. Future advances will continue to widen the possible samples that the microscope can be applied to: small, irregularly shaped objects, molecules only present in small amounts, looking at mixtures of particles or even molecules still present within cells.

The technique is already achieving results that were unthinkable a few years ago – both in terms of the small size of biological molecules that can now be imaged, and in the detail that can be seen in them. Future advances will continue to widen the possible samples that the microscope can be applied to: small, irregularly shaped objects, molecules only present in small amounts, looking at mixtures of particles or even molecules still present within cells.

James Streetley, Post-doctoral researcher, University of Glasgow

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.